Photographic film

Dan Tobias (Talk | contribs) (→References) |

Dan Tobias (Talk | contribs) (→References) |

||

| Line 60: | Line 60: | ||

* [http://www.democratandchronicle.com/article/20130613/BUSINESS/306130045/Kodak-ending-acetate-base-manufacturing?gcheck=1 Kodak ending acetate base manufacturing] | * [http://www.democratandchronicle.com/article/20130613/BUSINESS/306130045/Kodak-ending-acetate-base-manufacturing?gcheck=1 Kodak ending acetate base manufacturing] | ||

* [http://thisisnthappiness.com/post/53216073756/film-canisters-print Picture: film canisters] | * [http://thisisnthappiness.com/post/53216073756/film-canisters-print Picture: film canisters] | ||

| + | * [http://boingboing.net/2013/06/27/the-history-of-aspect-ratios.html The history of aspect ratios (mostly in 35 and 70 mm movie film)] | ||

Revision as of 12:06, 28 June 2013

Photographic film was a popular medium for photography throughout the 20th century, replacing earlier forms of photography using plates which held a single image (which go back to the mid 19th century), and rapidly losing ground to digital photography in the early part of the 21st century.

Film starts out in unexposed form, ready to be used to take pictures, and stored in a casing which keeps out light, since any exposure to light outside the controlled exposure through a camera lens will ruin the film, which is highly sensitive to light. The camera pulls the film from its case onto a reel, placing the film one frame at a time in a position to be exposed to an image from the camera lens when the shutter button is pushed. When all the film has been used to take pictures, it is rewound back into its casing where it can be removed from the camera without exposing it to light, since it is still sensitive at this point. It must then be developed using a chemical process in a darkroom (so named because it is not lit, except by special lights using wavelengths the film is not sensitive to). Once the developing is finished, the film is no longer light-sensitive and can be stored and viewed under normal light.

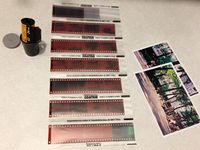

Exposed and developed photographic film may be encountered as a file format either in negative -- a color-reversed state from which prints may be produced on photographic paper -- or as a transparency that can be viewed directly (with the naked eye, or more typically, with backlighting and magnification) or projected with a projector. The primary identification of photographic film formats is by size. Additional distinctions include black-and-white vs. color, as well as film speed (how sensitive it is to light, affecting how long of an exposure is needed to get a usable image).

Photographic film is encountered in still formats (typically, a single image) and movie formats (strips of film transparencies with numerous sequential images designed for the projection of moving pictures). Some movie formats designed for exhibition also encode audio data (soundtracks) on film alongside the sequential images. Other movie formats were intended for exhibition with simultaneous audio provided by a synchronized separate recording. There were also "silent movies" which had no audio, but typically a musician such as a piano player performed while the film was played.

Contents |

Still-picture negative formats

- 110 film

- 120 film (and 220)

- 126 film

- 127 film

- 35 mm negatives (135)

- Sheet film

- Disc film

Slide formats

Instant formats

Filmstrip formats

Movie formats

Film technologies

References

- Photographic film at Wikipedia

- Sound film at Wikipedia

- Death of film

- 100 ideas that changed photography

- Pinhole camera created with 3D printer

- 100 history-making cameras on a poster

- Kodak ending acetate base manufacturing

- Picture: film canisters

- The history of aspect ratios (mostly in 35 and 70 mm movie film)